A compounder sees white residue on freshly extruded PVC profiles. Assuming plasticizer migration, they reduce the plasticizer level by 5 phr. Two weeks later, the bloom is worse, and the profiles have become brittle. The actual cause was lubricant excess – and reducing plasticizer was exactly the wrong move.

This scenario happens more often than it should. Lubricant blooming and plasticizer blooming produce similar-looking surface defects, but they require opposite corrective actions. Treating one as the other makes the problem worse. Before adjusting your formulation, you need to identify which additive type is actually migrating.

How to Identify the Blooming Type

The surface appearance and texture tell you which additive category is responsible. Lubricants and plasticizers have fundamentally different polarities and carbon chain structures, which produces distinct bloom characteristics you can assess on the production floor.

| Characteristic | Lubricant Bloom | Plasticizer Bloom |

|---|---|---|

| Appearance | Whitish, waxy, matte, hazy | Oily, greasy, shiny, wet-looking |

| Texture | Dry, powdery, slippery | Tacky, sticky, oily |

| Wipe test | Comes off as powder or wax | Leaves oily residue on finger |

| Timing | Often temperature-triggered | Gradual over storage time |

| Location | Surface film only | Surface and may penetrate adjacent materials |

Lubricants have lower polarity and longer carbon chains than plasticizers. This makes them inherently less compatible with the PVC matrix – they are the “least compatible constituent” in most formulations and most prone to surface migration. Plasticizers, by contrast, are designed for matrix compatibility but can still migrate when molecular weight is too low or when in contact with absorbing materials.

Before reformulating, stop and identify. I have seen too many cases where compounders assumed plasticizer migration because it is the more commonly discussed problem, only to make the bloom worse by reducing plasticizer and leaving the actual lubricant issue untouched.

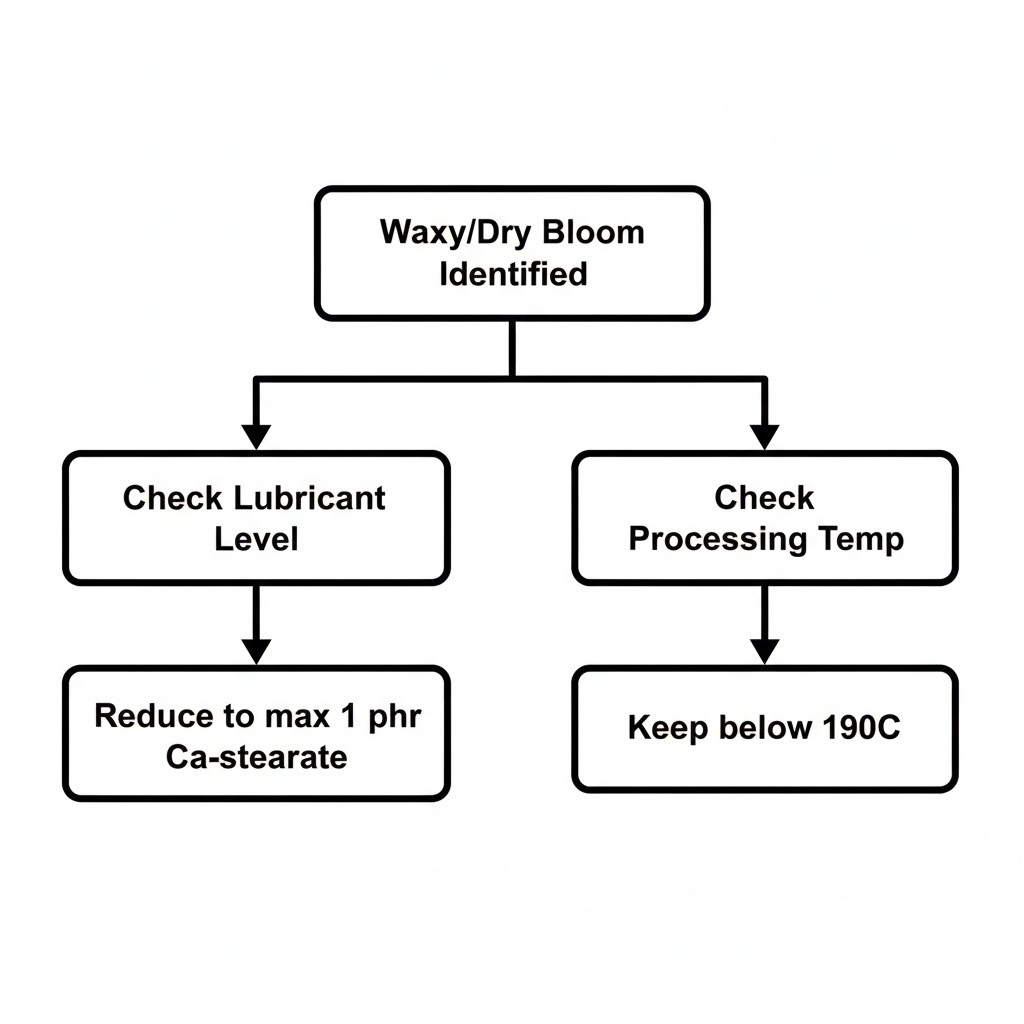

Correcting Lubricant Bloom

If the bloom is waxy, dry, and comes off as powder, you are dealing with lubricant excess or incompatibility. The corrective action is to reduce the lubricant level or switch to a more compatible lubricant type.

For rigid PVC applications, calcium stearate should not exceed 1 phr. Above this level, the lubricant accumulates at the surface rather than functioning as a processing aid. At processing temperatures above 190C, calcium stearate can also undergo phase inversion – transitioning from a continuous coating around PVC particles to a discontinuous phase within the matrix. This causes melt fracture, rough surfaces, and reduced impact strength.

A documented case illustrates how lubricant bloom behaves differently from plasticizer migration. PVC dolls manufactured with stearyl alcohol as a processing lubricant developed white crystalline bloom during cold storage. When returned to room temperature for one month, the stearyl alcohol was almost completely reabsorbed into the PVC matrix. Temperature decrease had reduced compatibility, promoting exudation – but the effect was reversible.

If you see waxy bloom on rigid PVC, check your calcium stearate level first. It is the most common culprit. For flexible PVC, examine whether external lubricant levels are within the 0.2-1.0% range.

Correcting Plasticizer Bloom

If the bloom is oily, tacky, and leaves a greasy residue, you are dealing with plasticizer incompatibility or low molecular weight. The corrective action is to switch to a higher molecular weight plasticizer – not to reduce the plasticizer level.

Reducing plasticizer to address bleeding sacrifices flexibility without solving the migration problem. The plasticizer is migrating because of insufficient molecular weight or poor compatibility, not because there is too much of it.

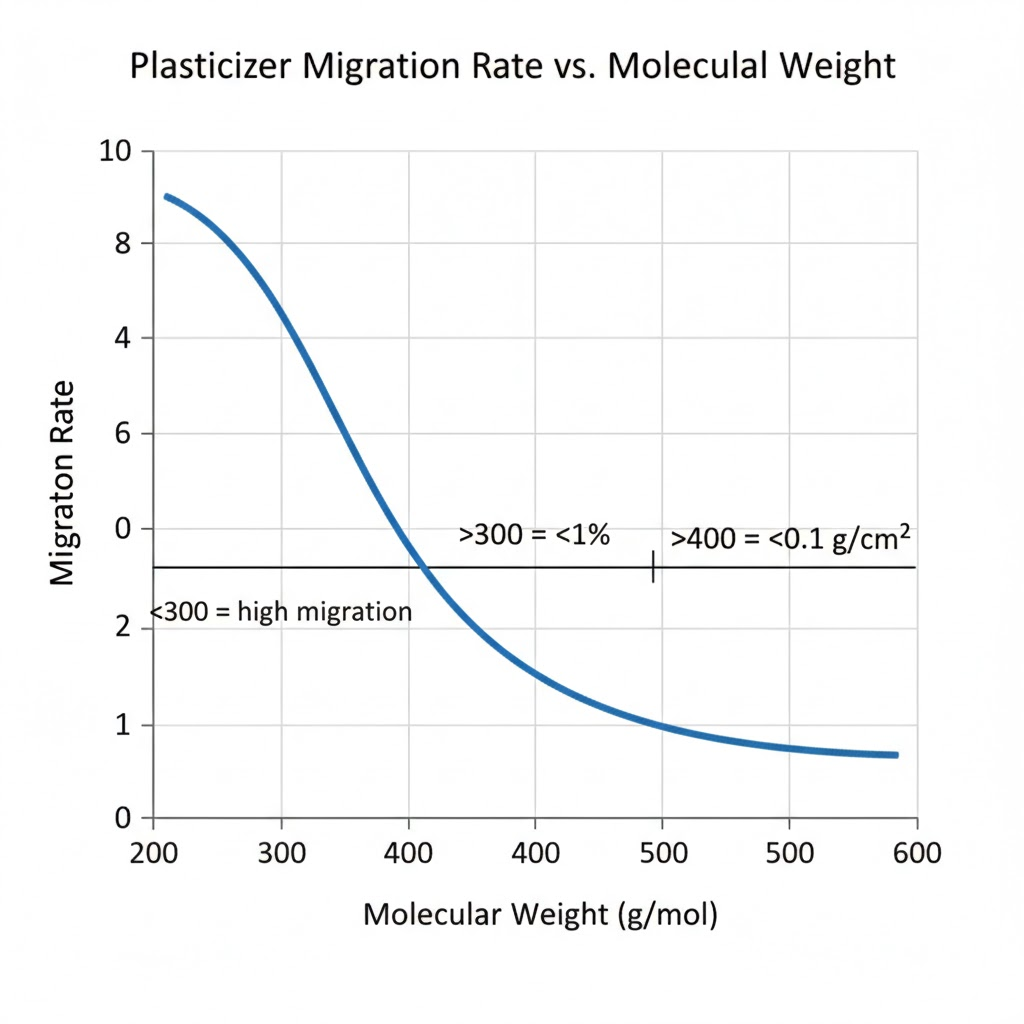

Molecular weight thresholds matter:

- At MW greater than 300 g/mol, migration drops below 1%

- At MW greater than 400 g/mol, migration rate falls below 0.1 g/cm2

- Low MW plasticizers under 300 g/mol can migrate 10 times faster than high MW alternatives above 500 g/mol

Molecular structure also affects migration. DOA (MW 371) migrates about twice as fast as DOP (MW 390) despite similar molecular weights, because DOA has a linear structure while DOP is branched. Branched molecules become more entangled in the polymer network and resist migration.

For applications requiring lower migration rates, consider switching from DOP to higher molecular weight alternatives. DINP, DOTP, and TOTM offer progressively better migration resistance. Polymeric plasticizers with molecular weights above 2000 provide the lowest migration rates but require processing adjustments.

Adding 4-7 wt% micro-calcium carbonate can also reduce migration by creating a tortuous diffusion path, with weight loss under 0.5% in testing.

Never reduce plasticizer to fix bleeding – you will sacrifice flexibility and still have migration. Switch to a higher MW type or add barrier fillers instead.

Verification and Prevention

After implementing corrective action, verify the fix with accelerated aging. Store test samples at elevated temperature for one to two weeks and examine for bloom recurrence. If the issue was correctly diagnosed and corrected, bloom should not reappear.

For complex cases where visual identification is inconclusive, analytical confirmation via FTIR or GC-MS can identify the specific migrating compound. This is particularly useful when multiple additives are under suspicion or when the formulation is unfamiliar.

Document what you changed. Most recurring blooming problems I encounter come from undocumented formulation drift – small adjustments made without records that compound over time until the formulation moves outside its stable operating window.

Prevention comes from tracking both formulation ratios and processing parameters. Lubricant bloom is often triggered by temperature excursions during storage or processing. Plasticizer bloom is accelerated by contact with absorbing materials or extended high-temperature exposure. Knowing what changed helps diagnose future problems faster.

Conclusion

The diagnostic step is what separates effective troubleshooting from trial-and-error. Both bloom types produce similar surface defects, but the physics behind them differ completely – and so do the solutions. Getting the identification right prevents the scenario where your fix makes the problem worse.